Software systems exhibit a peculiar property: the more sophisticated they become, the more they tend toward catastrophic rather than graceful failure. This pattern isn’t unique to software - it’s characteristic of all complex systems, from neural networks to financial markets. But software’s rapid evolution and ubiquity makes it a particularly interesting case study.

A complex system isn’t merely complicated. Rather, it possesses specific properties that make its behavior fundamentally unpredictable:

- Dynamic interaction between components that can’t be reduced to simple cause-and-effect relationships

- Feedback loops that create non-linear responses to changes

- Emergent properties that can’t be predicted from analyzing individual components

- Nested complexity where components themselves are complex systems

Consider a seemingly straightforward example: running a persistent database on Kubernetes. At first glance, this might appear to be just a collection of software components working together. But examine it more closely:

- The database must maintain consistency across distributed nodes

- Kubernetes continuously adjusts resource allocation based on load

- Network latency creates feedback loops affecting query performance

- Storage systems interact with hardware in non-linear ways

- Each layer (database, Kubernetes, cloud infrastructure) is itself a complex system

The result isn’t just a complicated stack of technology - it’s a system where changes in one component can propagate in unexpected ways, creating emergent behaviors that weren’t designed or anticipated.

Richard Cook’s “How Complex Systems Fail” makes a counterintuitive claim: complex systems are always running in a partially broken state. This isn’t a flaw in implementation, but rather an inherent property of complexity itself. Why?

- The number of potential interactions between components grows factorially with system size

- Each interaction represents a potential failure mode

- Testing all possible states becomes computationally intractable

- Individual “minor” flaws are too numerous to fully eliminate

- The system continues functioning despite these flaws due to human adaptation

This leads to what we might call the “complexity paradox”: as systems grow more sophisticated in an attempt to prevent failures, they become more complex, which in turn makes them more prone to catastrophic failure modes.

The pattern becomes clearer when we examine how defenses against failure evolve:

- Technical defenses (redundancy, monitoring, automated recovery)

- Organizational defenses (procedures, certifications, audits)

- Human defenses (training, expertise, tacit knowledge)

Each layer of defense adds complexity, creating new potential failure modes even as it guards against known ones. The result is a system that appears more robust to anticipated problems while becoming more vulnerable to “black swan” events - rare but catastrophic failures that emerge from unexpected interactions between components.

When catastrophic failures occur in complex systems, organizations typically respond with a search for the “root cause” - a fundamentally flawed approach that misunderstands the nature of complex system failures. These failures aren’t linear chains of causation but rather emergent phenomena arising from multiple interacting components and conditions. What makes a failure “catastrophic” rather than routine is not merely its impact, but its emergence from the subtle interplay between system components, creating cascade effects that overwhelm our carefully constructed defenses.

The impossibility of truly isolating root causes becomes clear when we consider the nature of complex systems: they are constantly evolving, operating with multiple simultaneous flaws, maintained by changing combinations of human and technical components, and subject to different environmental conditions at different times. The very notion of “cause” in such systems may be more a human construct than a meaningful description of system behavior.

A particularly insidious aspect of complex system failures is what we might call the “hindsight fallacy” - the tendency to view past failures as obviously predictable once we know their outcome. This creates a dangerous illusion of preventability that drives misguided remediation efforts.

Consider a Kubernetes cluster where application pods suddenly lose database connectivity due to an underscaled load balancer. Post-incident, the solution appears obvious: “We should have scaled the load balancer.” But this apparently simple insight obscures the reality of operating complex systems. The actual system state before failure was far more ambiguous, with multiple potential failure points existing simultaneously. Resources and attention were finite and had to be allocated across many concerns. The relationship between load balancer scaling and system stability wasn’t necessarily clear in advance.

The natural response to such failures is often automation - an approach that introduces what Cook and Parameswaran independently identify as a profound paradox. By attempting to prevent specific failure modes through automation, we paradoxically increase system complexity, create new potential failure modes, reduce operator engagement with the system, and mask accumulating problems until catastrophic failure occurs.

Take the load balancer example: Implementing autoscaling seems like an obvious solution, but it introduces new complexities in configuration, documentation, monitoring requirements, and potential failure modes. Perhaps most critically, it reduces operator familiarity with manual scaling procedures. Over time, operators interact with the system less frequently, their skills atrophy, and the system becomes progressively less legible to human understanding.

The paradox of automation extends beyond merely increasing system complexity. In “The Control Revolution and Its Discontents”, Ashwin Parameswaran identifies a more subtle and pernicious effect: automation’s apparent safety creates an environment where human error can accumulate invisibly. By smoothing over minor issues and handling routine failures, automated systems mask the early warning signs that would traditionally alert operators to deteriorating performance.

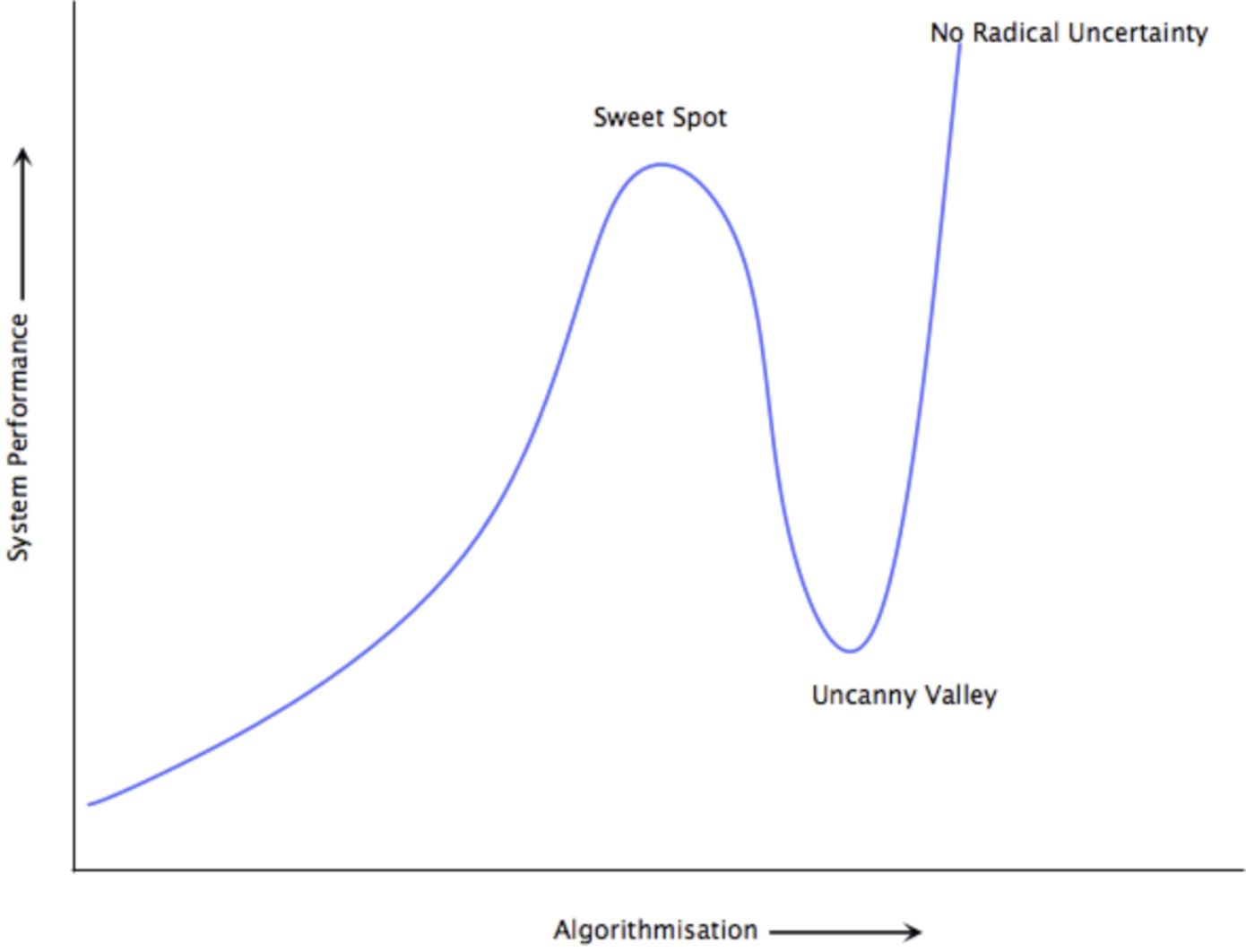

This leads to what Parameswaran calls the “uncanny valley” of automation - a state where the system appears more reliable in normal operation, but operators become progressively deskilled and the potential for catastrophic failure actually increases. The system becomes a black box, operating in ways that are increasingly opaque to the humans nominally in charge of maintaining it.

An instructive analogy is that of self-driving cars. Early automotive automation - cruise control, lane assistance - augments human capability without introducing significant new risks. A sweet spot emerges where the machine handles routine tasks while the human driver remains engaged and capable, hands on the wheel, ready to respond to situations requiring judgment. The uncanny valley begins when automation extends into critical scenarios, fostering dangerous overconfidence in drivers who have grown complacent yet must still intervene in emergencies. Only true level 5 autonomy, with its complete elimination of uncertainty, would justify removing the human driver entirely.

Parameswaran’s analysis of the Air France Flight 447 crash in 2009 provides a haunting illustration of the uncanny valley in automation. In his essay “People Make Poor Monitors for Computers”, he shows how the automated systems that were meant to make the flight safer ultimately contributed to its catastrophic failure. The pilots, accustomed to the plane’s sophisticated autopilot handling most situations, found themselves suddenly forced to take manual control in challenging conditions. Their skills, dulled by routine reliance on automation, proved inadequate for the crisis they faced.

What lies beyond the uncanny valley of automation? In principle, a state of perfect algorithmization where radical uncertainty has been eliminated entirely. This represents the ultimate goal of the “control revolution” - that centuries-long project to solve every problem through data and algorithms. In such a world, omniscient AI systems would handle all complexity, and human operators could take a much needed sabbatical.

How should we approach automation in complex systems, knowing that perfect algorithmic control remains aspirational? Parameswaran suggests a nuanced strategy: embrace automation for non-catastrophic failures while maintaining redundancy where failures could prove ruinous. This keeps human operators meaningfully engaged while benefiting from automated assistance. The goal is not to eliminate human involvement but to structure it properly - maintaining the feedback loops that build and preserve operator capability.

Cook arrives at similar conclusions through different reasoning. He argues that safety emerges from operators’ intimate familiarity with failure modes and system boundaries. Effective monitoring systems should help operators recognize the “edge of the envelope” - that threshold beyond which system behavior becomes unpredictable. This requires not just data collection but careful design of human-machine interfaces that make system state and trajectories legible to operators.

The fundamental insight is that safety isn’t a product to be purchased or a feature to be coded - it’s an emergent property arising from moment-to-moment adaptation by skilled human operators working with automated systems. Until we achieve true algorithmic omniscience (if ever), our focus must be on maintaining this creative tension between human and machine capabilities, keeping operators firmly within the loop while leveraging automation to extend rather than replace their capabilities.