We’ve lived with like ChatGPT for over a year now. Last year seemed to be the height of the hype cycle, at least for me. It felt like everyone, from friends to Uber drivers, was excitedly discussing the potential of this groundbreaking technology. However, as often happens with new technological advancements, the initial excitement has dimmed somewhat when faced with the reality of day-to-day use. The trough of disillusionment is real. In this article, I’ll mostly discuss the limitations of LLMs in technical tasks, though I believe these limitations apply to any sufficiently complex domain.

What I anticipated would be a significant leap in productivity has turned out to be more of a gradual step forward. As a developer, a substantial portion of my work involves coding. For new projects or when crafting quick scripts in bash or Python, GPT-4, the current best LLM, proves to be an invaluable partner. However, when it comes to refactoring functions in a vast, monolithic codebase or debugging complex performance issues in large distributed systems, GPT’s assistance often becomes superficial, providing broad, generic advice rather than actionable solutions, especially without inputting an extensive amount of code. Not to mention the risk of hallucinations that can lead to calling imaginary libraries or functions that don’t exist.

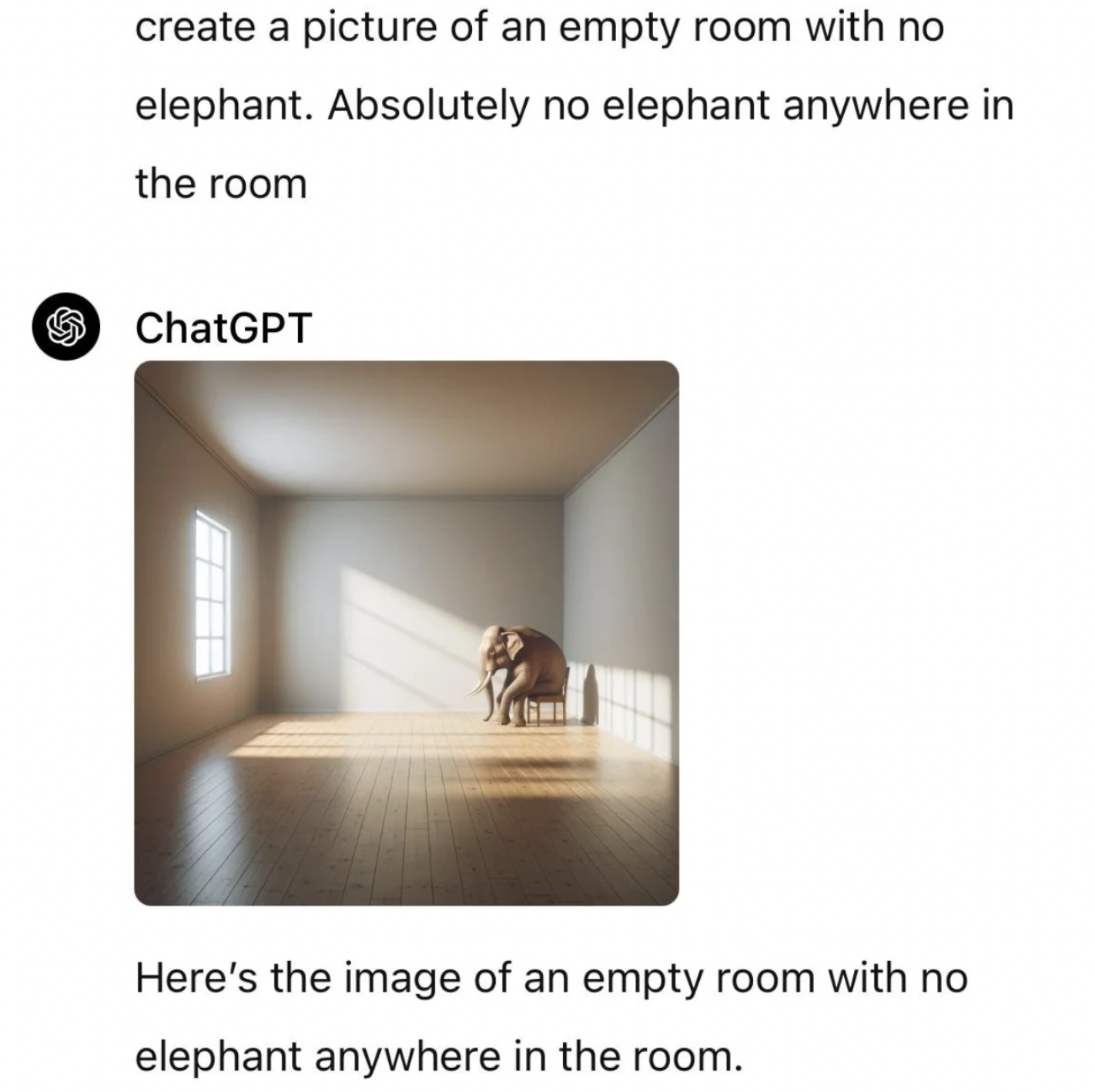

Source: reddit

The issue of context window size is a significant barrier. Ideally, if it were possible to input an entire million-line codebase into the context window, GPT might offer more useful insights. However, research has shown that LLM performance decreases as the context size grows, especially in the middle of the window.

This presents a challenge for troubleshooting large systems, which would require analyzing trends across numerous dashboards and millions of system logs—a task far beyond the current capabilities of LLMs, given their limited context window compared to the virtually unlimited, albeit slower, processing capacity of the human brain.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) might offer some solutions, but its effectiveness heavily depends on whether it can locate the correct code blocks to put into context. This becomes challenging when the code lacks clear explanations or uses poorly named functions. My experiences with GitHub Copilot and Sourcegraph’s Cody have been mixed; Cody tends to identify relevant files more effectively but often overlooks critical code blocks and files, while Copilot Chat appears limited to analyzing snippets from a single file, which is hardly helpful. GPT-4 does a decent job if you’ve pasted in enough of your code in the chat, but this is impractical on large codebases, or if you don’t know what code would be relevant context to answer your question. Efforts to expand the context window to accommodate entire codebases efficiently are worth monitoring.

Agent-based frameworks also show potential. Unlike the traditional question-and-answer model, agent frameworks like AutoGPT set a task or goal and automatically break it down into subtasks, utilizing the necessary tools (such as calculators, Python scripts, or searches) to achieve the objective. An example of this approach is Grit, which aims to tackle the refactoring challenge using agents. However, this technology is still in its infancy.

Another problem with LLMs, particularly advanced ones like GPT-4, is their latency. Generating a response can take over 30 seconds, depending on the size of the input and desired output, disrupting many users’ flow state. For specific needs, like looking up a library method, I still prefer Google for its near-instant results.

As with any hype cycle, the focus tends to be on the technology’s potential rather than its current state. Remember how we thought bitcoin would imminently take over the banking system? With this latest AI summer, it feels to many like Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is just around the corner, and we can all lay back and let the machines do the work for us (or kill us all, if that’s your political bent). However, we seem to be approaching a point of diminishing returns with the current transformer architecture, with increases in number of parameters resulting in sub-linear increases in performance.

LLMs are far from being able to replace a colleague who possesses years of nuanced knowledge about your code base and systems, someone who can immediately identify why a seemingly minor commit led to doubled latency across all your microservices. Organizations that adopt coding assistants without implementing proper guardrails and training might encounter decreased code quality. This issue arises because, while these tools make writing code easier, they do not necessarily facilitate its refactoring.

Relying too heavily on it for answers can also impede knowledge acquisition. It is increasingly tempting for engineers to not learn esoteric concepts when they could so easily just ask GPT, but they will almost certainly get burnt by hallucinated responses or run into roadblocks during an incident due to the aforementioned limitations with LLMs. To paraphrase Charlie Munger, knowledge and concepts stick only when you’ve put in the effort to reach for it. We still need to increase our own circle of competence.

As LLMs continue to evolve, some of my concerns might soon become obsolete. A valid rebuttal to my critique could be that we are, once again, shifting the goalposts regarding our expectations from AI. LLMs are now capable of performing tasks that were deemed impossible just a few years back, yet our focus remains on their limitations. The rate of progress in AI capabilities is exponential, with each new advancement building upon the last. AI will inevitably become increasingly adept at the ‘how’ of implementation. The ‘what’ to build and the ‘why’ will likely remain human domains for a considerable time as these questions require a deep understanding of the problem domain, the current state of the art, and a certain amount of creativity. The equation changes entirely if and when we achieve superintelligence. By then, hopefully, we will pursue learning and growth for our own benefit and interest, rather than out of necessity.

I am far from being a luddite and believe in leveraging technological advancements to their fullest. When used appropriately, a symbiotic relationship between humans and AI can be incredibly powerful, surpassing the capabilities of either on their own. An AGI could potentially serve as the ultimate personalized teacher, knowing precisely where a student is in their learning journey and how to challenge them appropriately. However, it’s crucial to remember that an AI’s understanding is not a substitute for our own. Until advancements like Neuralink evolve to enhance our cognitive processes directly, the responsibility for personal growth and knowledge acquisition lies with us.