Joshua Foer’s “Moonwalking with Einstein” is one of the rare books that I found worth rereading. In it, Foer, a young journalist, enters the bizarre world of memory competitions after being assigned to cover the world championship. He describes in vivid detail the unusual characters he encounters, mnemonic techniques he learns, and books he reads to help prepare him for the U.S. Memory Championship. The “memory athletes” he interviews are able to memorize a deck of cards in thirty-two seconds, recall over eighty thousand digits of pi, and recite the entire works of Shakespeare. Foer’s efforts pay off, and he becomes the U.S. Memory Champion by the end of the year.

The History of Mnemonics

The ancient Greeks and Romans lacked modern technologies for storing information outside their minds. Most people were illiterate, and written books were rare. Socrates even opposed written language, arguing it would leave men’s minds empty as they wouldn’t need to retain what they learned. Instead, these cultures relied on mnemonic techniques to memorize speeches and epic poems. “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” feature vivid descriptors like “rosy-fingered dawn” and “weeping Aphrodite” because such imagery aided memorization. In “Ad Herennium,” Cicero’s treatise on rhetoric, he includes a brief section on mnemonic techniques. Foer refers to this work as the “bible” of memory competitors.

Some ancient figures were reportedly capable of truly astounding feats. Pliny the Elder writes: “King Cyrus could give the names of all the soldiers in his army. Lucius Scipio knew the names of the whole Roman people. King Pyrrhus’s envoy Cineas knew those of the Senate and knighthood at Rome the day after his arrival. A person in Greece named Charmadas recited the contents of any volumes in libraries that anyone asked him to quote, just as if he were reading them.”

Mnemonics in Modern Times

Rote memorization was a staple in education until relatively recently. Students were required to memorize historical dates, multiplication tables, Latin vocabulary, and other facts. Educators believed the value of this practice lay not only in learning the information but also in training the ability to memorize.

Eventually, memorization came to be seen as dehumanizing. Schools systematically deprioritized it in favor of more “experiential learning.” Foer laments that we are now in a state where most high school students can’t identify when the Civil War occurred, and 20% of students can’t even name the countries the U.S. fought in World War II.

When exactly did educators remove advanced mnemonic techniques used by the ancients from the curriculum? Given their effectiveness, one would expect these methods to have been favored over rote memorization. While the book doesn’t directly answer this question, it offers some hints.

The Science of Memory

As a rule, humans have a working memory capacity of 7 bits of information, plus or minus 2. This explains why phone numbers are 7 digits long (excluding area and country codes), and why license plates are of similar length. Huberman offers a working memory test on his podcast. It didn’t surprise me to learn that I have a below-average working memory capacity of 5, at least according to his test (perhaps explaining my need to reread this book!).

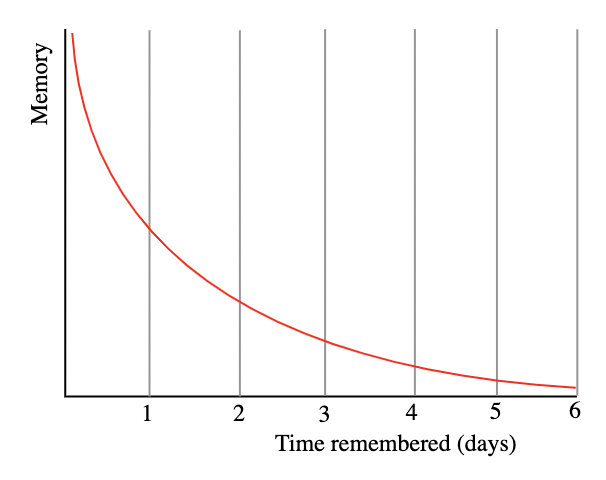

While you might have suspected your memory to be unreliable, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus used science to confirm it. In the late 19th century, he discovered the “forgetting curve” by memorizing 2,300 three-letter nonsense syllables and testing his recall at various intervals. His experiments demonstrated that memory retention decreases exponentially over time. This finding also led to the concept of spaced repetition, as the frequency of reminders needed to retain information also decreases exponentially. This principle is why I use Anki, a topic I’ll explore in another blog post. Ebbinghaus unfortunately did not repeat the experiment using mnemonic techniques in order to see the impact on the forgetting curve, but one suspects the curve will be less dramatic.

Source: Wikipedia

Mnemonic techniques work exceptionally well because they leverage the human brain’s natural tendencies. Humans possess remarkable spatial memory. According to Foer, we can “learn and recall the layout, dimensions, decoration, and contents of a house, including the location of hundreds of objects, without consciously realizing it.” The concept of the memory palace exploits this ability to store and organize information.

Human memory is deeply associative. It’s far easier to remember information when it has something to “cling” to. This characteristic explains why knowledge compounds: the more you know, the more you can learn. Mnemonic techniques aim to create artificial associations to enhance retention.

Mnemonic Techniques

Foer mentions several mnemonic techniques in the book. Below is an overview of those that left the strongest impression on me.

Memorable Visual Representation

The human mind is far more adept at recalling images than names and numbers. The fundamental principle underlying most mnemonic techniques is to create memorable visual representations of the information you want to retain.

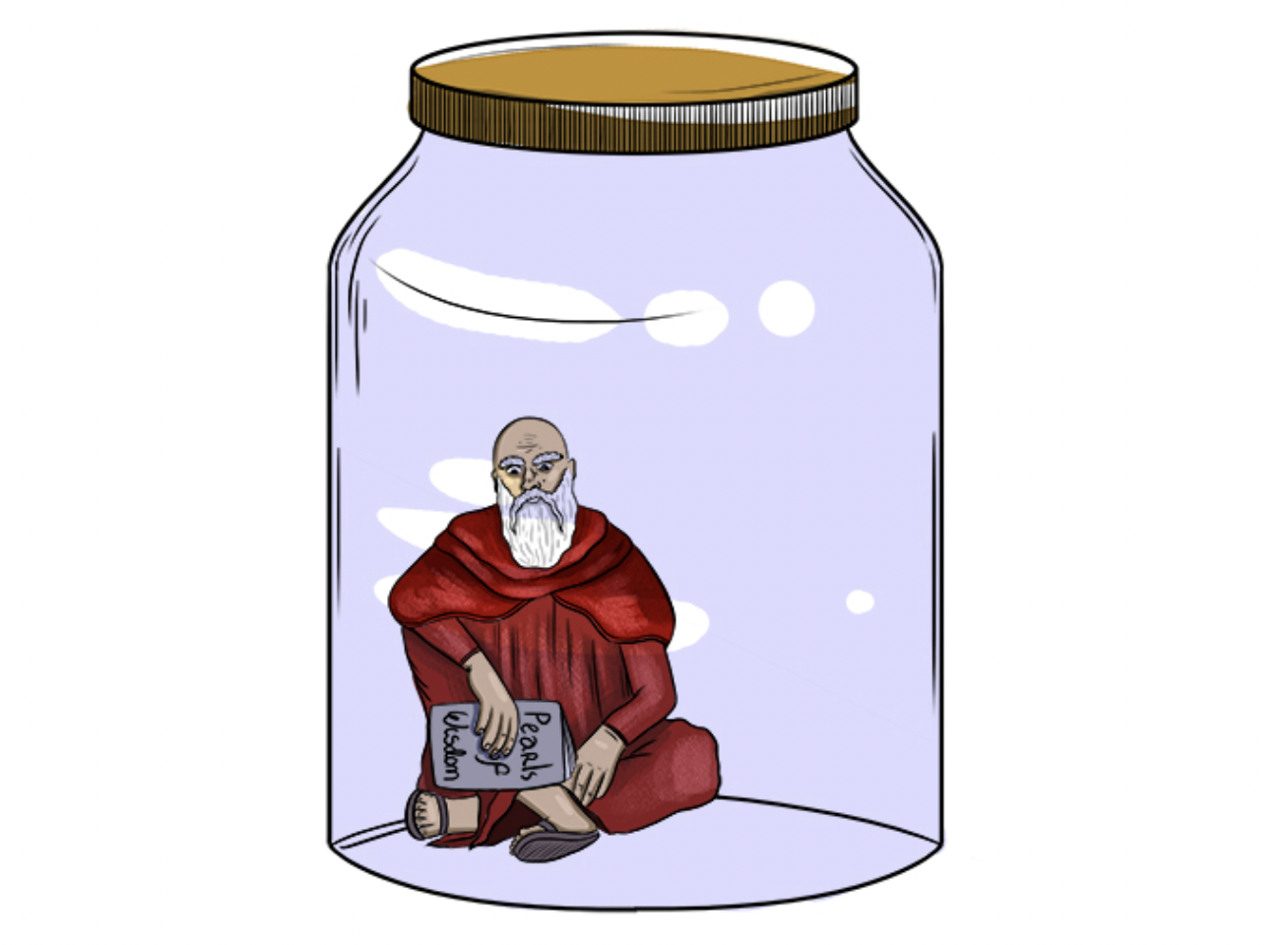

For example, to remember the definition of “hermetically” (meaning “in a way that is completely protected from outside influences”), you might visualize a hermit sealed in a glass jar.

Source: Mammoth Memory

Memory Palace

The memory palace technique dates back at least to ancient Rome, believed to be invented by Simonides of Ceos around 500 BCE. It exploits the human brain’s capacity for remembering spatial information.

The first step is to construct a “memory palace.” This need not be a literal palace; the most effective locations are those you know well, such as your home, office, or college dorm.

Imagine you have a grocery list with the following items: rice, milk, salmon, broccoli, ginger, lentils, and curry paste. The concept involves placing each item within your “memory palace” in bizarre and memorable scenarios.

For instance, you might envision:

- Your front door covered in a pile of rice, with rice raining down on you.

- Several people in your entryway sporting milk mustaches, asking “Got milk?”

- You open the door to your bedroom to find the bed replaced by a giant fish tank full of jumping salmon.

Using this technique, you can more easily recall each item in the list, as well as the order of items.

I’ve encountered several challenges in fully utilizing memory palaces. One significant issue is the surprising difficulty in creating large memory palaces. I’ve attempted to make one based on my usual neighborhood walk. While it’s easy to recall major landmarks like the park or ice cream shop, retaining more objects requires remembering finer details. I find myself questioning: Did the house with wooden shingles precede or follow the Victorian? How many houses stood between the park and Lombard Street? Maybe the ancient Greeks simply possessed a superior memory for spatial details, at least compared to me.

Another challenge is that memory palaces resemble linked list data structures in computer science. In linked lists, each element contains a pointer to the next element in sequential order. This structure has several drawbacks, including the need for sequential access, and inefficient insertion and deletion in the middle of the list. Similarly, if you forget a location in your memory palace, recalling the rest of the list becomes more challenging. Retrieving a memory from the middle of the palace might require starting from the beginning, slowing down recall . If you realize you need to add an item in the middle of your palace, you might need to shift all of the following items in your palace. Also, most information I want to remember doesn’t require exact sequential order.

I’ve found memory palaces useful for various uses, such as recalling the main points of a presentation or managing task lists associated with specific responsibilities. For example, I use my office building as a memory palace for work-related tasks, and the route to the grocery store for shopping lists.

Here’s a more detailed guide on memory palaces if you want to explore further: https://artofmemory.com/blog/how-to-build-a-memory-palace/

The Major System

The Major system is designed to help remember numbers, something that we are usually terrible at. Its core principle involves associating each digit with a specific phonetic sound, then transforming numbers into words that incorporate these sounds.

Each digit maps to phonetic sounds as follows:

- 0 -> s, z

- 1 -> T, D, Th

- 2 -> N

- 3 -> M

- 4 -> R

- 5 -> L

- 6 -> Ch, J

- 7 -> K

- 8 -> F, V

- 9 -> P, B

The Wikipedia page has a more comprehensive description.

Using this mapping, you can transform numbers like 31415 into vivid imagery: MaT (31) covered in RaTs (41) chased by an eeL (5). As with the memory palace technique, the more unusual the imagery, the more effective it is.

The Major system’s primary advantage lies in its simplicity. Once you’ve memorized the digit-to-sound mapping, you can apply it to any number you wish to remember.

This was the main mnemonic technique that remained with me since my previous reading of Foer’s book. It can significantly enhance recall of short number sequences. I’ve successfully used it to remember lock combinations, dates, and the last four digits of credit card numbers.

The PAO System

The Major system becomes less effective when dealing with truly large numbers, such as one hundred digits of pi. This is where the PAO (Person-Action-Object) system comes into play. Be warned: beyond this point lies the domain of serious memory geeks. During my previous reading of Foer’s book, I stopped practicing mnemonics at this point.

The PAO (person-action-object) system is designed to help memorize very long numbers, decks of cards, or really any other long sequence of elements. A standard version of it maps each number from 00 to 99 to a person, an action, and an object. For example, the number 42 might be Ron Burgundy, cooking, and hammer. To remember a longer number like 429087, one would create a vivid mental image combining the associated elements: Ron Burgundy (42) cooking (90) a dish of hammers (87).

A significant drawback of the standard PAO system is the arbitrary nature of its subject-to-number mappings. For a two-digit system, this requires memorizing 300 distinct associations before one can fully use the system.

To work around this, one can combine the Major system with the PAO system. Using my previous example of 42, one could employ RoN Burgundy for the person, RuNNing for the action, and wReNch for the object. This approach significantly eases the memorization of mappings, though it comes with the trade-off that some numbers are hard to map to words or names, such as 88. In these cases, I simply chose something approximate or easily visualizable that wasn’t already assigned. In these cases, I simply chose something approximate or easily visualizable that wasn’t already assigned. This helpful blog post describes a Major PAO system in more detail.

I also realized that no PAO system can be universally effective. For optimal results, it must be tailored to be memorable for you specifically. If someone suggests using GeNe Wilder for 62, but you’re unfamiliar with him, that association becomes effectively useless to you. The people you select must be ones you can visualize easily. For example, while you might be aware of Enrico Fermi, if you can’t picture his appearance, he would be a poor choice for your system.

Mindfulness

An implicit element in all these mnemonic techniques is mindfulness. Applying any of these methods requires focusing on the subject for at least a brief moment. As I practiced these techniques, I discovered that even a weak encoding significantly enhanced my retention compared to my default strategy of making a “mental note” (assuming I was mindful enough to do even that). You can’t remember what you never paid attention to in the first place.

The Value of Mnemonics

While preparing for the U.S. Memory Championship, Foer begins to question the relevance of mnemonic techniques. He wonders if these ancient methods are “fascinating for what they tell us about the minds of a bygone era, but as out of place in our modern world as quill pens and papyrus scrolls.” Even Francis Bacon believed that “the art of memory was fundamentally ‘barren’”.

An relevant case study is that of Kim Peek, the individual who inspired the movie “Rain Man.” Peek possessed a genuine photographic memory, having memorized Shakespeare’s entire corpus. He could read two pages simultaneously, using each eye independently, at a rate of ten seconds per page, and had read over nine thousand books. One might expect such capabilities to lead to extraordinary success. However, Peek had an IQ of just 87 and significant neurological and physical abnormalities. His case demonstrates that a powerful memory alone is insufficient for worldly success, at least in our current society.

We live in an era of abundant and increasingly affordable external storage. One might question the need to memorize anything when we can ask Siri to set a reminder or jot down a note on our phones. Is memorizing ten thousand digits of pi or the order of a deck of cards anything more than an elaborate party trick?

One compelling argument for cultivating our memories is that they constitute the essence of our personal identity. Foer notes that some memory athletes he encountered, including Ed Cooke, maintained that “memory training was considered a form of character building, a way of developing the cardinal virtue of prudence and, by extension, ethics.”

Foer discusses the case of Henry Molaison, widely known as “H.M.,” one of neuroscience’s most extensively studied patients. Molaison underwent a radical surgical procedure in an attempt to cure his severe epilepsy. While the surgery alleviated his epilepsy, it left him unable to form new long-term memories, a condition known as anterograde amnesia. His memory remained frozen at the point of his surgery. This raises a profound question: Is it possible for an individual like Molaison to develop as a person without the ability to form new memories?

Foer also argues that the perceived dichotomy between “learning” and “memorizing” is false. Effective learning, he contends, necessitates memorization, and when done properly, memorization inherently involves learning. He cites chess grandmasters as an example: studies have shown they typically possess average IQs, with their primary differentiator being their robust memories of past chess games. Expertise, in general, hinges on the ability to recognize familiar patterns and subsequently apply appropriate solutions — a concept Malcolm Gladwell explores in his book “Blink.”

Memory may also play a crucial role in innovation. The term “invention” shares a common etymological root with “inventory.” To invent, one first needs a comprehensive inventory, or repository, of previous innovations and knowledge stored in memory.

Personally, I have found the mnemonic techniques described in this book to be beneficial, despite having a heavily customized Obsidian vault and an established Anki spaced repetition practice. There will always be information that is advantageous to recall without resorting to a smartphone. Additionally, there are often facts I need to retain temporarily before having an opportunity to record them. While I would readily adopt more advanced technologies like Neuralink once they become viable, until then, I’m continuing to develop my PAO system.

Conclusion

Foer’s whirlwind tour through the history of mnemonics and modern memory competitions is more engaging than one might anticipate. The book leans towards journalistic narrative, featuring interviews with intriguing characters, rather than delving deeply into the science behind memory. Nevertheless, Foer’s immersion in the world of memory competitions and his ultimate victory attest to the effectiveness of the mnemonic techniques he describes.

The question of a good memory’s ultimate value in today’s age remains open for debate. Although Foer himself appears to question the worth of mnemonics, I personally find significant value in the ability (or even the attempt) to quickly commit to memory that which I deem important. “Moonwalking with Einstein” is as an accessible introduction to mnemonic techniques that readers can immediately put into practice, while also providing references for those wishing to explore the subject further.