Nvidia is one of the largest companies in the world, frequently taking the top spot. It’s revenue is growing at an astonishing rate, with margins better than a lot of pure software businesses - something usually unheard of for hardware companies. All of this is on the back of a massive AI hype cycle. During a gold rush, you should sell picks and shovels. Nvidia is selling bulldozers. In this post, I will dive into the components of Nvidia’s competitive moat, its strengths and weaknesses, and the competitors trying to cross it.

In a capitalist system, profits are always competed away, unless you’ve managed to create a legal monopoly (i.e. power companies, Google). Nvidia does not have a monopoly, but they do have a near impenetrable moat.

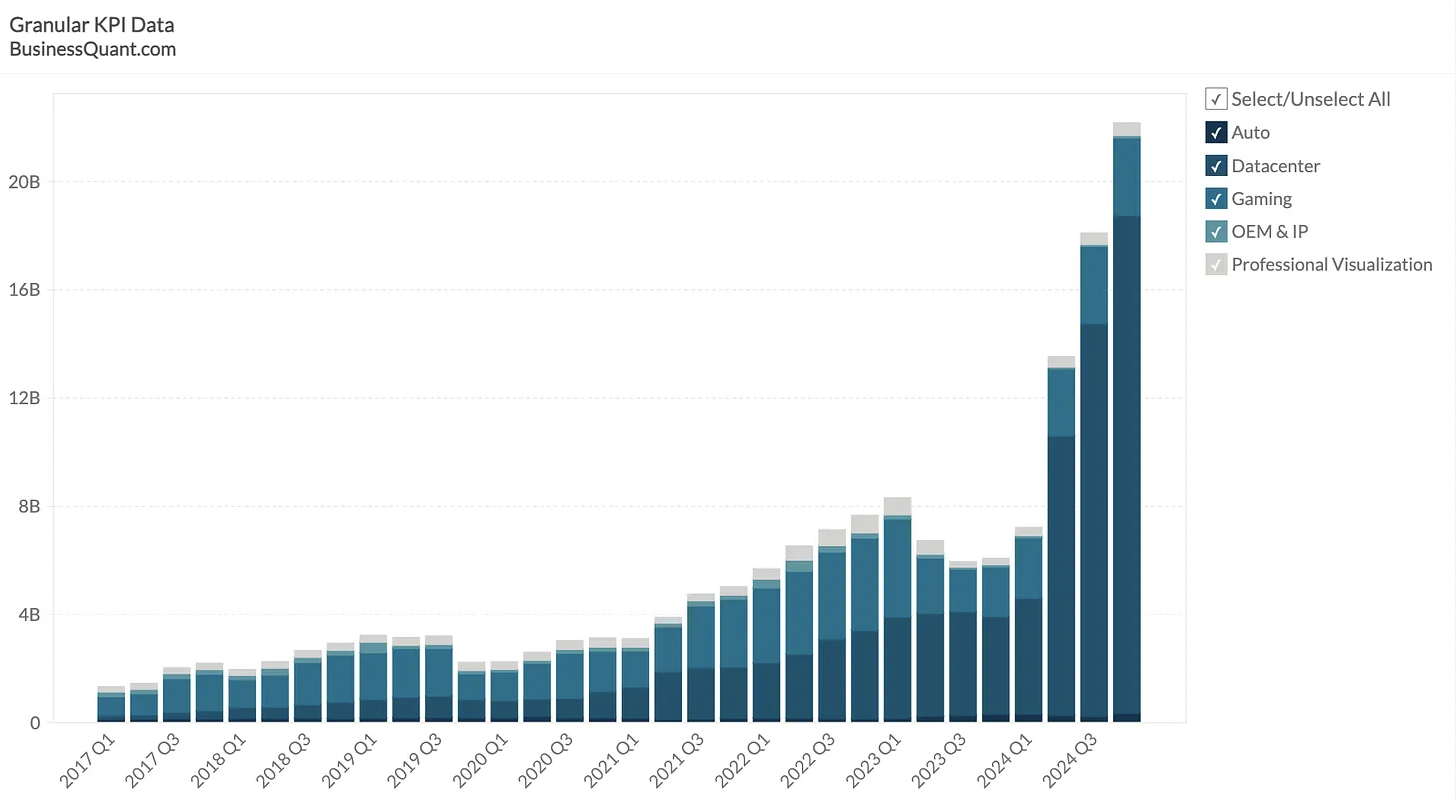

Today, consumer GPUs make up just a fraction of Nvidia’s revenue. The vast majority of it comes from their data center business. Very large companies with massive data centers like Tesla, Meta, and OpenAI (the “hyperscalers”) are in an arms race to acquire the currently scare resource that is Nvidia GPUs, which are, for now, basically the only game in town for AI training hardware. And because of that, Nvidia can charge exorbitant amounts for their GPUs. Nvidia’s margin of 71% is larger than most SaaS companies, something previously unheard of for hardware companies selling commodities.

Source: https://www.investmentideas.io/p/nvidia-pivoting-towards-chiplets

So how did Nvidia get into this enviable position?

Most of it comes down to the foresight of Nvidia’s founder Jensen Huang. He realized that GPUs could be used for scientific computing and started building CUDA even before there were real use cases. Through a stroke of good luck, the creators of AlexNet thought to use Nvidia GPUs and CUDA to train a model that won the ImageNet competition in 2012. This marked the beginning of the deep learning revolution. Deep learning is “embarassingly parallel” problem, and GPUs are perfectly suited to parallel processing.

A Primer on GPUs

A bit of an aside on CPUs vs GPUs (graphics processing units), and why GPUs are so much better for modern AI.

To help you develop a grossly simplified mental model, I will provide an analogy. Say you have to deliver a ton of coffee beans from Guatemala to Miami. You could use a jet (the CPU) which can carry one bag of beans (data) from the warehouse (memory) very quickly to and from Miami.

Or you can use a cargo plane (a GPU), which can carry a ton of bags much more slowly. The jet is optimized to prioritize latency (or speed), while the cargo plane is optimized to prioritize cargo capacity (memory bandwidth).

Smaller coffee shops that require different types of beans might benefit more from the jet since they need a small amount delivered quickly. This represents the general compute that a CPU is tasked with. Large coffee chains like Starbucks just need a consistent amount of the same beans in bulk. This represents the high bandwidth parallel processing required from the GPU.

When training a model, you need to run a single operation, usually matrix multiplication, on a large amount of data. The GPU, with its memory bandwidth, is much better suited to this task than the CPU. The tradeoff is that each individual task is slower, but you can simply add more parallelism (i.e., cargo planes).

GPUs, or graphics processing units, used to only be used for, well, processing graphics. Rendering graphics requires parallel processing and would be too slow to do on a CPU. Jensen’s insight was that this parallelism would be useful for tasks other than graphics processing, namely scientific computing. But in order for end users to be able to take advantage of the GPU for tasks other than gaming, they needed a programmable software interface on top of the GPU. That is where CUDA, or Compute Unified Device Architecture, comes in.

CUDA

Nvidia created CUDA before knowing whether there would even be a significant market for it. Their competitors, such as AMD, completely ignored this development. With AlexNet, CUDA found it’s “build it and they will come” moment. Deep learning needed to be done on GPUs, and Nvidia GPUs were the only usable ones because they have CUDA.

Almost every deep learning library (PyTorch, TensorFlow, Keras, etc.) is built on top of CUDA. There is an entire ecosystem of guides, blogs, StackOverflow posts that support CUDA users. AI researchers looking to train a model or experiment with new types of models favor Nvidia because they want an out of the box solution to working with the GPU without having to waste their time. Unsurprisingly, CUDA only works for Nvidia GPUs and is closed-source. CUDA has created a network effect for Nvidia GPUs, as the value of each GPU increases as the number of users increases. Any rival to Nvidia needs to be able to convince users than their offering is enticing enough to forego this massive ecosystem.

CUDA is just one of several software products the company produces. One of the most exciting is Omniverse, which uses Nvidia hardware to create “world scale” simulations. Automakers for example are using this to create “digital twins” of their assembly lines, where they can perfect configurations in the digital realm before implementing them in reality, among other applications. The real value here is the ability to create synthetic data sets at scale. Quality data is one of the key scarce resources in developing AI models.

CUDA is of course not how Nvidia makes the bulk of its money. Nvidia is first and foremost a hardware company. They have been building GPUs for over three decades, and have perfected the art.

Nvidia Hardware

The current best Nvidia AI GPU is the H200. It has 141GB HBM memory with a total bandwidth of 4.8TB/s per GPU across six HBM3e stacks. HBM memory, which consists of three dimensional stacks of memory chips, represents the cutting edge in high bandwidth memory. In my earlier analogy, HBM memory would represent a much larger storage area in the cargo plane.

To put the 141GB of memory into perspective, I built an AI PC with a consumer grade RTX 4090 last year. It has 24GB of memory, and can only fit Llama with 7 billion parameters. The H200 can fit Llama with 70 billion parameters. It still would not fit Claude 3.5 which as 2 trillion parameters though, so you’d need to network multiple GPUs together.

At GTC 2024, Nvidia announced the B200 “Blackwell” GPU, and a GB200 “superchip”. The B200 has up to 20 petaflops of processing power and 192GB HBM memory. Training a 1.8 trillion parameter model (such as GPT 4) would only require 2,000 B200’s, whereas it would have taken 8,000 previous generation “Hopper” chips for the same task. All of this while consuming a fourth of the energy. Suggested retail price from Nvidia: $30,000 to $50,000 each. In comparison, AMD’s competing MI300X costs between $10,000 to $15,000. Interestingly, Nvidia is not increasing the price for the Blackwell class chips as much as expected.

These chips can also be networked together with a next-gen NVLink switch, which can connect up to 576 GPUs with 1.8TB/s bidirectional bandwidth.

Now that I have sung Nvidia’s praises, it’s time to explore the threats to their business

The Chiplet Threat

Nvidia GPUs have a monolithic architecture. They often feature a single large chip. This means that if there is any issue with a chip during manufacturing, the whole chip needs to be discarded. AMD is working on chiplets for GPUs, which are several smaller chips that are stitched together to make one big chip. They already do this for their CPUs. If a smaller chip has an issue, you can replace just that one chip, thereby increasing yields. This means AMD could make GPUs on par with Nvidia, but at lower cost.

Large chips are also starting to run into the lithographic reticle limit, whereby producing cutting edge chips at nanometer scale becomes exponentially more expensive and eventually physically impossible. Chiplets on the other hand are still far away from this limit. AMD has been making chiplets for a while already and has a bit of a process moat, since getting chiplet production right requires a lot of trial and error. Nvidia only recently started breaking up the monolithic chip in the Blackwell version, which is just two big chips stitched together. If Nvidia continues down the path of making monolithic chips, they risk disruption by chiplets.

Inference

Another opening for competitors is the difference in requirements for training AI models vs “inference”. In simple terms, training a model is the actual creation of the AI model. GPT is a trained AI model. Inference is the process of getting outputs from the trained model. When you ask GPT a question, that is inference. Training requires much more compute power than inference, while inference requires much lower latency. Nvidia GPUs are currently the best available for training, but are already outperformed on inference by competitors, such as Groq.

If the need for inference scales more than the need for training, AI infrastructure spend could start to flow away from Nvidia unless they can create a competitive inference solution. Nvidia does already have open source frameworks focused on inference like TensorRT and is touting the inference performance of their Blackwell chips, so they likely realize this threat.

The Open Source Threat

The crown jewel of Nvidia’s competitive moat, CUDA, is also coming under attack. As discussed earlier, CUDA is what currently makes Nvidia the default choice for AI researchers and model creators. It is part of what justifies Nvidia’s exorbitant margins. Nvidia’s competitors are finally starting to realize the leverage that can be gained from offering a library like CUDA. AMD’s CUDA alternative is ROCm. Unlike Nvidia, they have open sourced ROCm. If CUDA remains closed-source, the contributions of the open source community could eventually make ROCm a more attractive platform.

Vendor lock-in is when you are forced to stick with one vendor for a particular service. Most software company operators (and probably most business owners in general) would agree that vendor lock-in is bad, especially for a core component of your business. If you’re locked in, the vendor can charge a right arm for crappy service and you’d just have to take it. Currently, most companies in the AI space are locked in to Nvidia GPUs. They therefore have a huge incentive to either develop or fund alternatives.

A Bubble?

There is no question that we are in the middle of a massive AI bubble currently. AGI, a technology that, if manifested, could be the last technology we as a race would need to create, seems to be just around the corner. This has sparked a trillion dollar arms race among the largest companies in the world. For that spend, some would argue that we should have gotten more than a some chatbots and image generators. Sequoia’s David Cahn calls this a $600 billion dollar hole. Almost all of that money has flowed to Nvidia. LLMs using the transformer architecture need exponentially more parameters for near linear performance increase. If real enterprise value isn’t created relatively soon, the bubble will burst, resulting in a precipitous drop in revenue for Nvidia.

An analogous historical parallel to Nvidia is Cisco Systems. During the internet bubble, everyone was clamoring for Cisco networking hardware. This sent their stock surging over 1000x over a decade. However, the stock lost 88% of its value and has yet to reach it’s peak again over twenty years later.

TLDR

Nvidia is the big winner of the current AI hype wave. They have a seemingly insurmountable moat that is comprised of cutting edge hardware and the dominant software interface for it. The largest companies in the world are stocking up on this hardware at exorbitant prices to remain on the cutting edge. There are, however, significant threats to Nvidia’s continued dominance. Their monolithic chip strategy might hit a scaling wall, leaving them scrambling to catch up to chiplets. The demand for inference might outweigh that of training, requiring them to refactor much of their development pipeline. CUDA might be superseded by open source alternatives like ROCm, diminishing the need to stay on Nvidia GPUs - a trend that will likely have support from Nvidia’s largest customers. Finally, the current AI bubble could burst, resulting in significantly reduced spend on GPUs for AI use cases.