Regardless of your views on David Goggins, it’s undeniable that he possesses an extraordinary level of persistence and willpower. Not only did he complete the grueling BUDS training for the Navy Seals three times, but he also finished US Army Ranger School and Air Force Tactical Air Controller training. He set a world record by completing 4,030 pull-ups in just 17 hours. Beyond that, he has finished over 60 ultra-marathons, triathlons, and ultra-triathlons. Remarkably, he achieved all this despite facing a challenging childhood, poverty, and battles with obesity, asthma, depression, and a heart condition.

Goggins consistently pushes the limits of human endurance. His life story demonstrates that tenacity and willpower are not necessarily innate; anyone can develop them.

What distinguishes Goggins from the average individual could be rooted in the neurological underpinnings of willpower and tenacity, within brain regions called the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

The Neuroscience of Willpower

The aMCC and ACC, key components of the brain’s salience network, play crucial roles in recognizing reward-related feelings and assessing the effort needed to achieve certain goals. These regions sit at a central location in the brain and maintain robust connections to various areas involved in planning, motor control, and sensory processing. Researchers believe that this central positioning enables their critical roles in willpower and determining the effort required for specific rewards.

What role does the aMCC play in determining why some people give up when faced with a challenge while others persevere? Consider the last time you needed to use willpower, whether during the final mile of a run, while tackling a coding problem, or resisting a bowl of ice cream. You likely weighed the benefits against the drawbacks without even realizing it, before deciding whether to give up or keep going. The aMCC is believed to be crucial in this decision-making process.

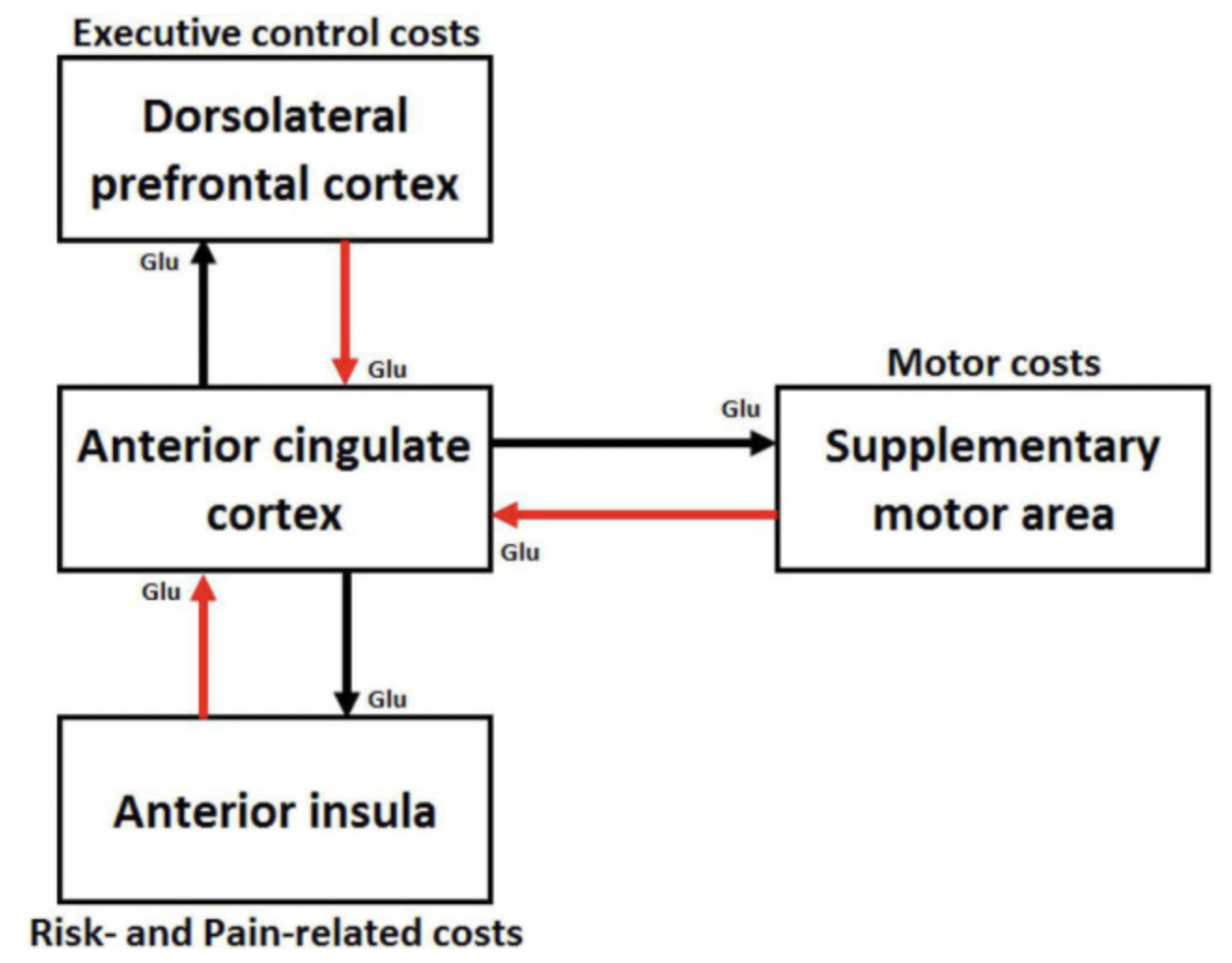

Willpower appears to involve balancing the perceived costs against the anticipated rewards. The ACC is key in assessing these costs, receiving cost estimates from various interconnected brain areas.

Illustration of cortical areas involved in effort cost estimation. The arrows indicate glutaminergic (Glu) pathways. Source: Training Willpower: Reducing Costs and Valuing Effort

The best proof of the correlation between the aMCC and willpower comes from stimulation studies, where the aMCC is electrically stimulated while behavioral response is measured. Stimulation of the aMCC was found to elicit various goal-directed behaviors. Another study found that patients had the feeling of “preparing for a difficult challenge”, and a “will to persevere” when their aMCC was electrically stimulated. They expected an imminent challenge, and had a determined attitude towards overcoming it. Check out the transcript of the fascinating interview.

Lesion studies in rats have shown that inactivation of their ACC causes them to decrease the amount of effort they were willing to expend for a reward. In humans, tumors pressing against the aMCC led to “indifference to the environment, change in personality or character, and a stuperous or comatose state”.

People with depression seem to have a reduced activation and size of the aMCC, thus leading to greater apathy. The severity of apathy was found to be correlated with decreased gray matter volume in the aMCC. Those with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease also displayed greater apathy.

Hopefully by this point you’re convinced of the link between the aMCC and willpower. How can we enhance the activation of the aMCC, thereby boosting our willpower?

Enhancing Willpower

Several studies seem to point to aerobic exercise as a key method to enhance willpower. One study of with fifty-nine older (60–79 years) and 20 younger (18–30 years) adults took part in a 6-month study in which they underwent aerobic exercise training. It found that the older participants had significant increases in brain volume, especially in the ACC. Previous studies have also shown that chronic aerobic exercise can lead to the growth of new capilaries in the brain, enhancing cognition.

“Superagers”, or elderly individuals whose cognitive performance is in some cases equivalent even to young adults, tend to have an aMCC of similar size to young adults. They often have a lifelong habit of aerobic fitness training. Another study found that aerobic exercise induced structural changes in the aMCC of adolescents that participated in 12 weeks of training.

Consistent effortful exercise leads to the reduction of the the estimated effort costs, due to increased connectivity between the ACC and other large scale networks. In other words, the more you exercise, the easier the same amount of exercise feels, establishing a “virtuous circle.” This cycle means training enhances your ability to exert effort, which in turn allows for more intense training and further boosts in willpower. Goggins’ remarkable achievements exemplify the extreme pursuit of this virtuous circle.

Another behavior that showed meaningful enhancements to the ACC was mindfulness meditation. One study found that mindfulness meditation improved bloodflow in the aMCC.

Conclusion

Although not everyone can or should reach the same level of willpower as David Goggins, the neuroscientific foundation of willpower and the effectiveness of behavioral interventions like aerobic exercise in strengthening it are evident. Starting a consistent exercise routine is one way to initiate a “virtous circle” leading to compounding benefits in terms of willpower and tenacity, helping individuals push their limits and achieve their goals.

Sources

- Aerobic Exercise Training Increases Brain Volume in Aging Humans

- Aerobic exercise impacts the anterior cingulate cortex in adolescents with subthreshold mood syndromes: a randomized controlled trial study

- An amygdala-cingulate network underpins changes in effort-based decision making after a fitness program

- Insights into Human Behavior from Lesions to the Prefrontal Cortex

- Motor and emotional behaviours elicited by electrical stimulation of the human cingulate cortex

- Neuroanatomical Characteristics of Geriatric Apathy and Depression: A Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study

- Short-term meditation increases blood flow in anterior cingulate cortex and insula

- The Will to Persevere Induced by Electrical Stimulation of the Human Cingulate Gyrus

- Training Willpower: Reducing Costs and Valuing Effort